One of the aspects that makes my style of training, the kind taught in Off The Floor, at The Movement Minneapolis, or in the Fitocracy PR Every Day coaching group so different is that there are no specified rep schemes. For some people, this represents a massive change in their way of thinking. If you have been accustomed to simply following a number of reps to do, it’s a tectonic shift.

The reason I don’t give reps is not that I am lazy or have some religious belief that prevents me from using numbers. The reason I don’t give reps is that I don’t know how many reps you need to do. I could tell you too few and I’d be doing you a disservice preventing you from maximizing your potential. I could tell you too many and you’d be pushing past your limits risking injury. As a coach I can sometimes judge when someone is going too far, but there are a myriad of sensations that you are privy to well before I can see when something is going wrong.

Believe it or not, you do know. But, it’s entangled with beliefs and a lack of understanding of the underlying reasoning. I think that widening the foundation of your understanding of what we’re trying to accomplish with various rep schemes can help people feel more comfortable in leading themselves.

Why do we do different rep schemes?

Put simply, different numbers of reps cause different physiological stresses. In the chart below I’ve noted some of the properties of doing different numbers of reps. I used Brad Schoenfeld’s 3 main mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and added two of mine own that relate more to strength adaptation without significant hypertrophy. These are gross generalizations and not to be taken as literal absolutist statements.

| Low Reps (1-3) | Mod Reps (5-10) | High Reps (15+) | |

| Metabolic Stress | Less | More | More |

| Mechanical Tension | More | More | Less |

| Muscular Damage | Less | Less | More |

| Connective Tissue Stress | More | Less | Less |

| Neurological Adaptation | More | Less | Less |

A caveat that I should note is that the rep ranges are based on an assumption that you are using a weight that you only able to do for that number of reps before reaching into excessive effort. You don’t get high connective tissue stress if you deadlift 5lbs for 3 reps unless you are an infant.

As you can see, low reps cause more of some types of phsyiological stress and high reps cause more in others.

Knowing what physiological stresses you’re going to bring about is about half of the puzzle. The other half is knowing the trade-off and the relationship between the different reps.

The biggest one I’d specifically like to address in this article is volume.

In case you’re not familiar with this term (you should be), volume is the total amount of work done. You can look at it per movement, or per workout. If you deadlift 225lbs 10 times you have 2250lbs of volume. If you deadlift 100 times you have 22,500lbs of volume.

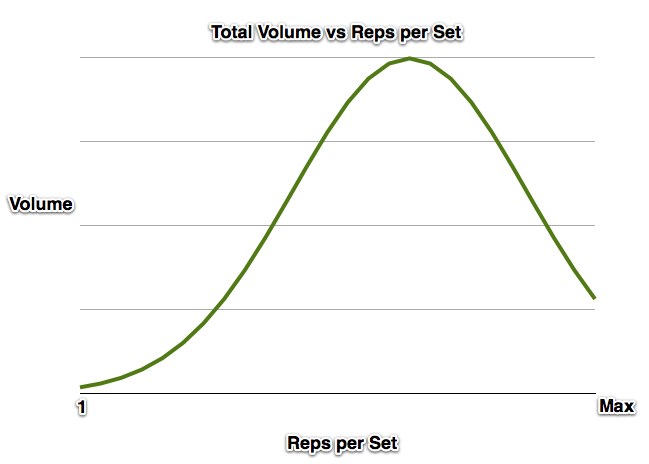

There is a bell-curved relationship between low reps, moderate reps, and high reps. See the chart:

Described verbally: at your lowest reps per set (singles) you will do very little total volume, perhaps only a few reps total. At the very highest reps per set, where you are hitting muscular failure on the first set, you may do a lot of reps but the resulting metabolic stress and muscular damage will prevent you from accomplishing much volume in subsequent sets.

Somewhere in the middle lies the sweet spot. There is a point at which the metabolic stress is mitigated, mechanical tension is moderated, and muscle damage is limited. This is the spot where you could seemingly do endless amounts of volume.

On either side of this point you also have a wide berth where you can achieve large amounts of training volume. These are the areas of the curve I encourage people to take advantage of and increase their training volume. Most people I work with are shocked at how much training volume they are actually capable of and likewise how little their current training programming actually consists of. Once you start doing 25,000lb workouts on the regular, you start realizing why you weren’t progressing with 8,000lb workouts. You are literally capable of so much more.

Programming physical training is a lot of science, with a hint of art in how you actually apply it. I think my friend Nick Tumminello said it well when he said “Training is the art of expressing the science.” As you’ve hopefully learned above there are different ways to accomplish the same thing with each variable affecting the others slightly. If you want to learn more about how to customize and individualize training programs from one of the very, very best keep in mind that Eric Cressey’s High Performance Handbook is only on sale through today. When someone has built their entire business on some of the very best athletes in the world getting results, coming back, and sending their teammates you can bet that you are going to learn something valuable. Plus, apparently Eric has extended the offer to win a trip to Cressey Performance so that is still up for grabs.

Go peep the High Performance Handbook.

Hey Dave, great article! However I’m not totally clear on something; what’s the primary benefit of training using the maximum volume you are capable of? Strength, mass, endurance, or the maximum mix of all these?

thanks

Glen, besides simply being more practice at your lifts there is more stimulus for adaptation. More all of the above really is the answer. Obviously there is a trade-off in terms of time invested and recovery, but I see most people at more risk of under-doing than over-doing their training volume.