Little kids don’t even know how good they have it. Someone cooks them three meals a day, not including snack time. They get to take exciting trips to the park and the library. Just about everything seems like the most exciting thing they’ve ever done, and the moment doesn’t fly by them. Above all though, they get naps. Oh, the naps. Nothing makes me more jealous of kids than the naps they begrudgingly get to take.

Naps are the miracle supplement of healthy, productive people and societies. People on the island of Ikaria, a place where they seemingly forget to die, living measurably longer than people anywhere else on earth, take long naps during the day. Geniuses like Einstein are known to have taken short naps throughout the day, Einstein was said to have held a pencil in his hand until he dropped it – waking him up the moment he entered the deepest sleep. Dogs nap every chance they get, and they’re the happiest creatures on earth.

I’m not a genius, or an Ikarian, but I’ve been able to reap the productivity and energy benefits of short naps in only 16 minutes a day. It’s simple, but like anything worth doing will take a little time to master.

Here’s what you do:

- Set an alarm for 30 minutes.

- Darken the room as much as possible. I nap on the massage table at the gym, or on a couch. Beds are for sleeping at night.

- Get comfortable, and warm. Ideally the room would be cool, and you’d have a blanket or something warm to cover your body.

- Close your eyes and and let your thoughts go. In the first few minutes, you’ll be thinking about work, relationships, bills, and everything else. Let those thoughts go, almost in a meditative way until you fall asleep.

- When you wake up in a fog, wondering if you fell asleep, you probably already did. Get up immediately.

- If your alarm goes off, whether or not you were sleeping or even fell asleep you are done for the day. Go on with your day.

- Repeat daily, or even throughout the day if time permits.

Most people won’t even fall asleep the first few times they try this, but with a little bit of practice you’ll find that you fall asleep quickly, probably within five minutes of closing your eyes. As an added bonus, you might find that you fall asleep more quickly at night as well.

You will find that you wake up feeling incredibly refreshed. I nap like this about two times per week, usually when I find that my afternoon grogginess is limiting my productivity or effectiveness. Those moments when you’re at your desk and you feel like you could just close your eyes and go to sleep are perfect.

One of the big advantages of a temp controller is that you never have to open the smoker to check anything. Keeping the lid closed keeps the temp stable and the smoke in. It’s not a cheap addition to your setup, but it’s worth it for the peace of mind and consistency.

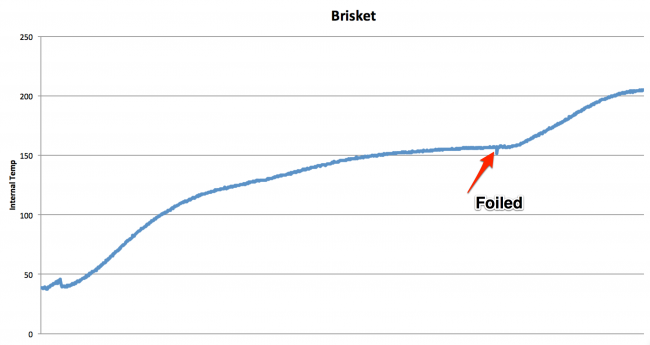

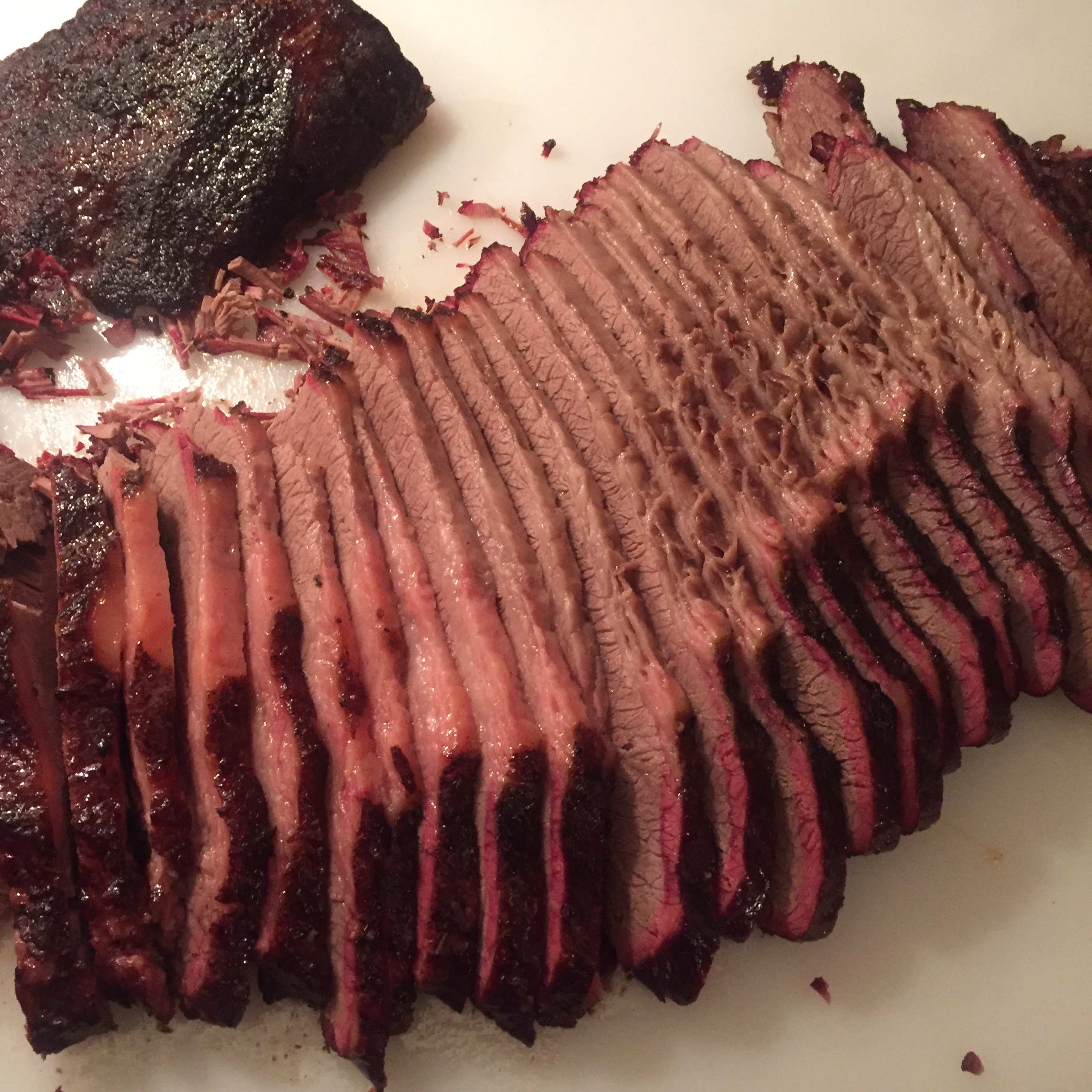

One of the big advantages of a temp controller is that you never have to open the smoker to check anything. Keeping the lid closed keeps the temp stable and the smoke in. It’s not a cheap addition to your setup, but it’s worth it for the peace of mind and consistency. nversion process, all the plateau is is the point at which evaporation of the water in the meat reaches an equilibrium with the low-temperature cooking and results in an almost constant state of evaporative cooling until you run out of water in the meat. Not great. Now, after several hours in the smoke when the meat hits a plateau (around 155ºF) I wrap it in aluminum foil for most of the remainder of the cook. This does two (well, three) things that are beneficial: you retain more water and moisture in the meat, you get a good cup or two of delicious juice to pour over the meat later (I happen to know that some fancy chefs dip their brisket in beef stock before serving to make it more juicy), and it usually signals that you’ll be done cooking in no more than a couple hours. Depending on timing I will sometimes kick the heat up to 250 or 275 at this point to speed things up as you’re not going to hurt the meat at that point.

nversion process, all the plateau is is the point at which evaporation of the water in the meat reaches an equilibrium with the low-temperature cooking and results in an almost constant state of evaporative cooling until you run out of water in the meat. Not great. Now, after several hours in the smoke when the meat hits a plateau (around 155ºF) I wrap it in aluminum foil for most of the remainder of the cook. This does two (well, three) things that are beneficial: you retain more water and moisture in the meat, you get a good cup or two of delicious juice to pour over the meat later (I happen to know that some fancy chefs dip their brisket in beef stock before serving to make it more juicy), and it usually signals that you’ll be done cooking in no more than a couple hours. Depending on timing I will sometimes kick the heat up to 250 or 275 at this point to speed things up as you’re not going to hurt the meat at that point.